A Brief Introduction to the ScaNN Index

ScaNN is Google’s answer to a familiar challenge in large-scale vector search: how to increase query throughput and reduce memory usage without taking an unacceptable hit to result quality. Conceptually, ScaNN starts from the classic IVF+PQ recipe—coarse clustering plus aggressive product quantization—but layers on two important innovations that meaningfully shift the performance frontier:

A score-aware quantization objective that better preserves the relative ordering of true neighbors, improving ranking quality even under heavy compression.

FastScan is a SIMD-optimized 4-bit PQ lookup path that reduces the traditional memory-load bottleneck by keeping more work inside CPU registers.

In practice, it is a strong choice when you are okay with trading some recall for high QPS and a much smaller memory footprint (often compressing vectors to ~1/16 of the original size), such as in recall-insensitive recommendation workloads.

In this post, we’ll revisit IVFPQ as the baseline, explore the key optimizations ScaNN introduces on top of it, and wrap up with experimental results that ground the discussion in measured performance.

IVFPQ Recap

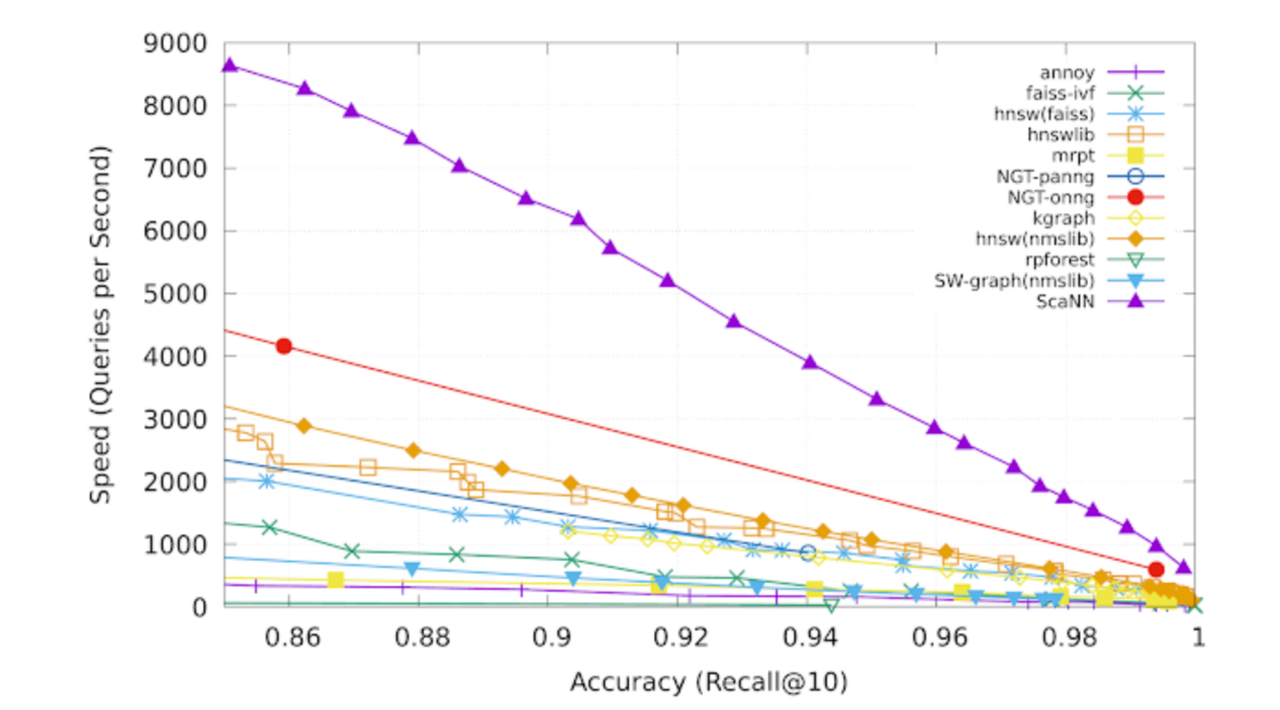

ScaNN was proposed by Google in 2020, and the paper reports a 3× performance improvement over HNSW on the GloVe dataset. You can refer to the original paper and the open-source implementation for details.

Before introducing ScaNN, we’ll briefly recap IVFPQ, since ScaNN is built on top of the same overall framework.

IVFPQ stands for Inverted File with Product Quantization, an algorithm used for efficient and large-scale Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) search in high-dimensional vector databases. It is a hybrid approach that combines two techniques, the inverted file index (IVF) and product quantization (PQ), to balance search speed, memory usage, and accuracy.

How IVFPQ Works

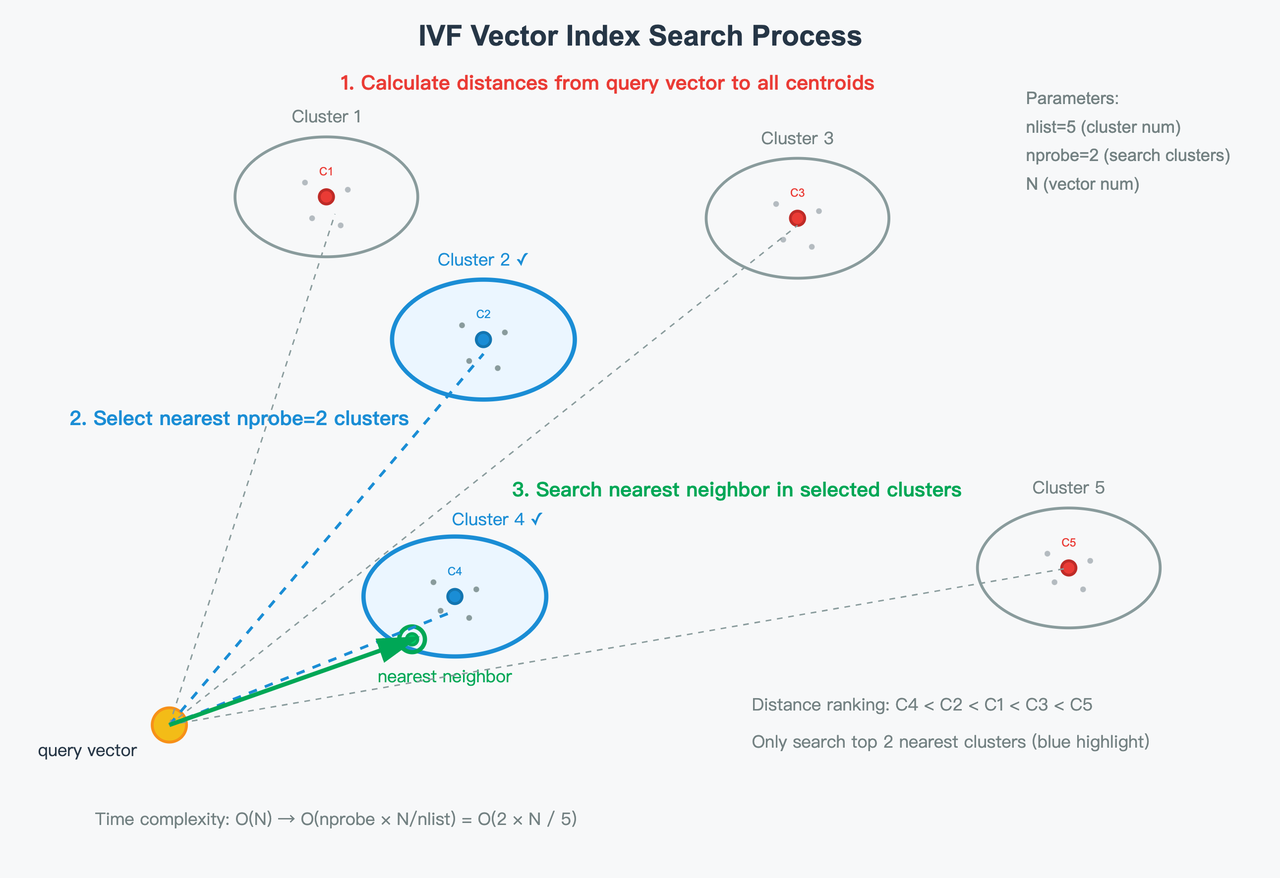

The process involves two main steps during indexing and searching:

- IVF layer: vectors are clustered into

nlistinverted lists (clusters). At query time, you visit only a subset of clusters (nprobe) to trade off recall and latency/throughput.

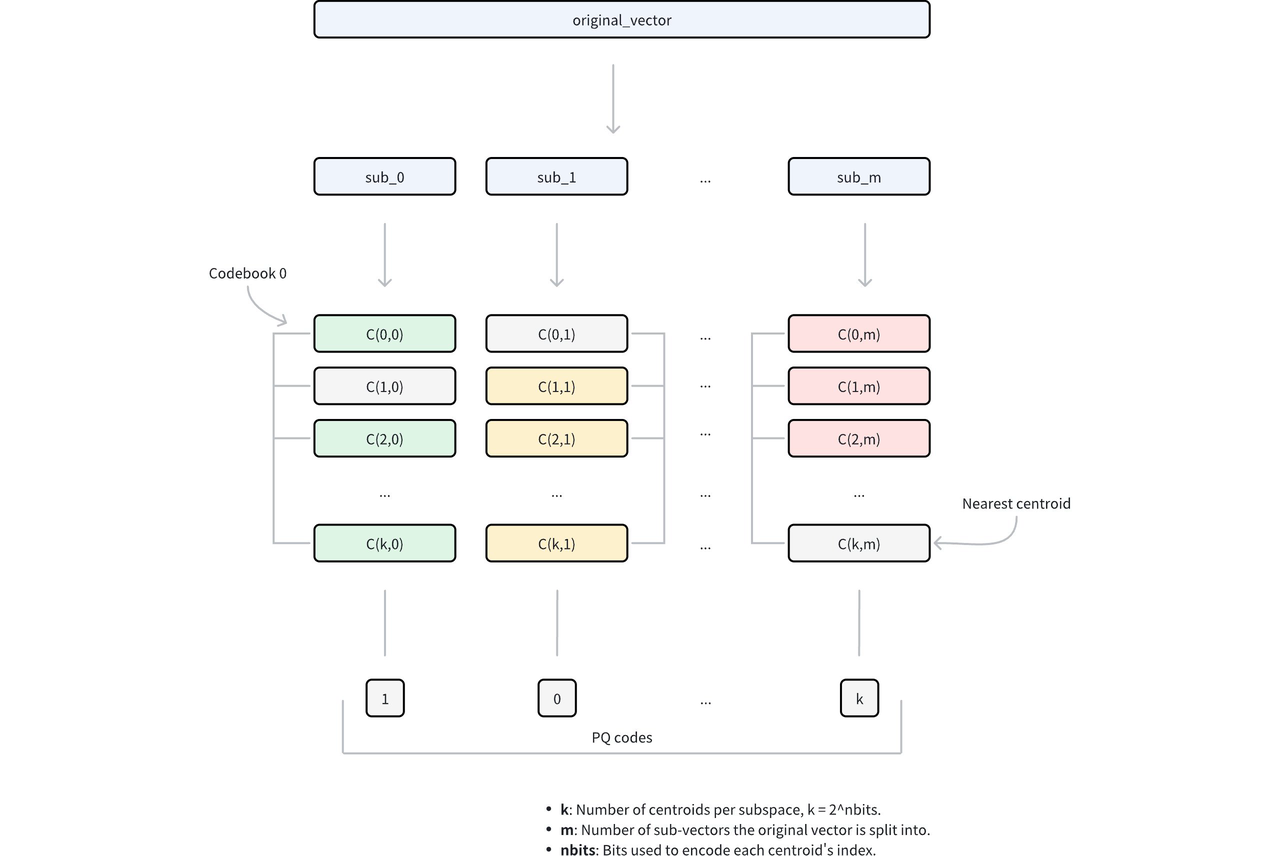

- PQ layer: within each visited cluster, each D-dimensional vector is split into m subvectors, each of dimension (D/m). Each subvector is quantized by assigning it to the nearest centroid in its sub-codebook. If a sub-codebook has 256 centroids, each subvector can be represented by a

uint8code (an ID in [0, 255]).

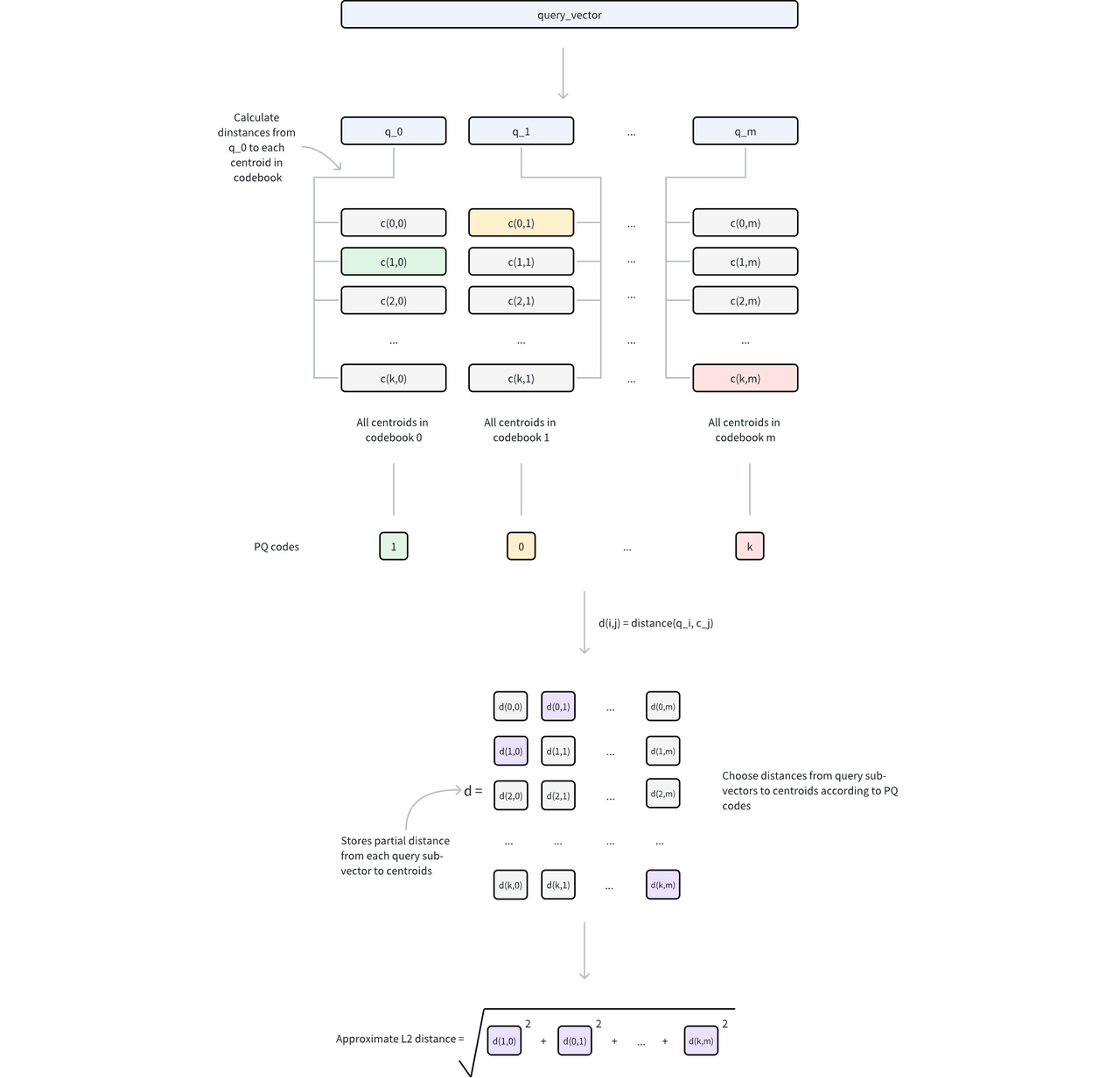

Distance computation can then be rewritten as the sum over subvectors:

D(q, X) = D(q, u0) + D(q, u1) + D(q, u2) + … + D(q, un)

= L(q, id1) + L(q, id2) + L(q, id3) + … + L(q, idn)

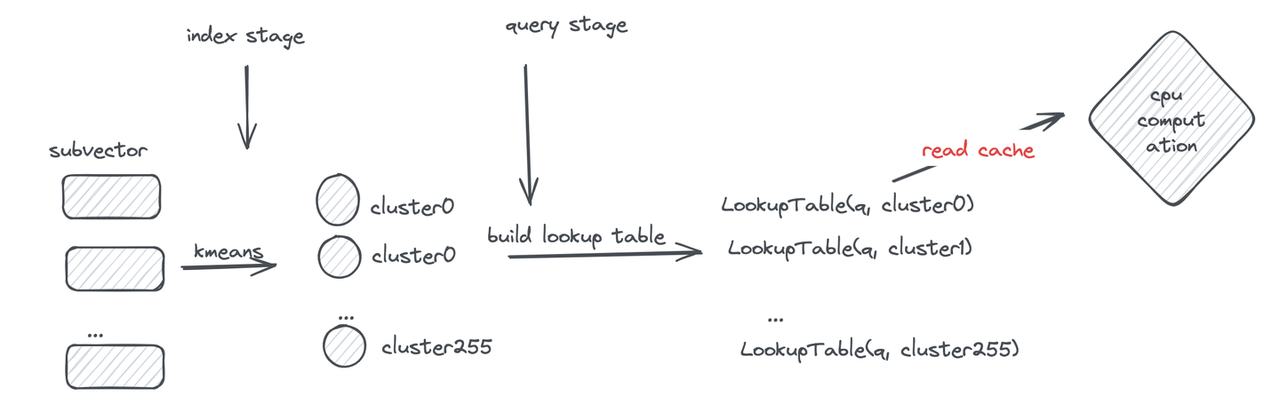

Here, L represents a lookup table. At query time, the lookup table is constructed, recording the distance between the query and each quantized subvector. All subsequent distance computations are converted into table lookups followed by summation.

For example, for 128-dimensional vectors split into 32 subvectors of 4 dimensions each, if each subvector is encoded by a uint8 ID, the storage cost per vector drops from (128 x 4) bytes to (32 x 1) bytes—a 1/16 reduction.

ScaNN Optimizations Based on IVFPQ

In summary, ScaNN improves IVFPQ in two aspects:

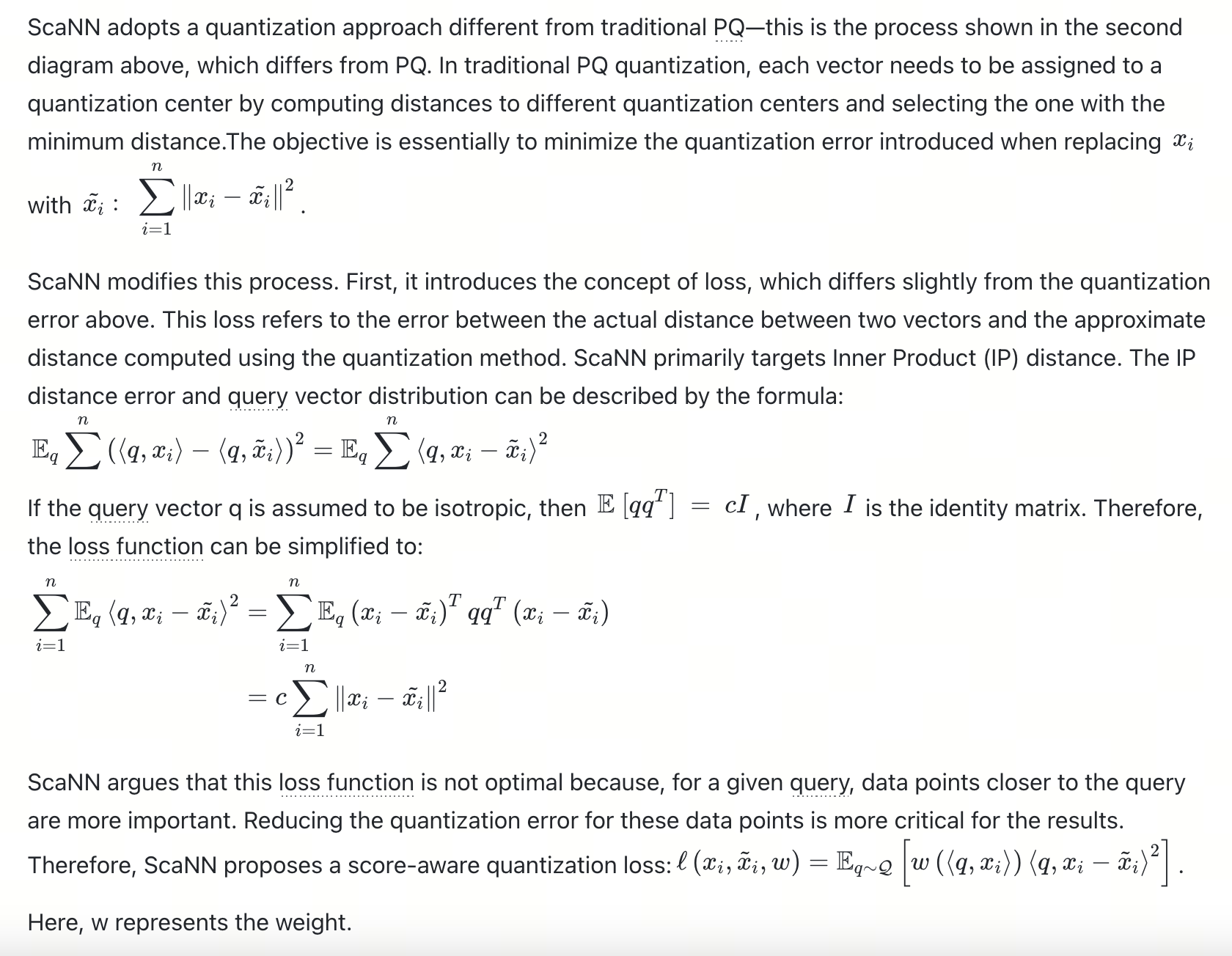

Quantization: ScaNN proposes an objective beyond simply replacing each subvector with its nearest k-means centroid (i.e., minimizing reconstruction error).

Lookup efficiency: ScaNN accelerates LUT-based search, which is often memory-bound, via a SIMD-friendly FastScan path.

Score-aware Quantization Loss

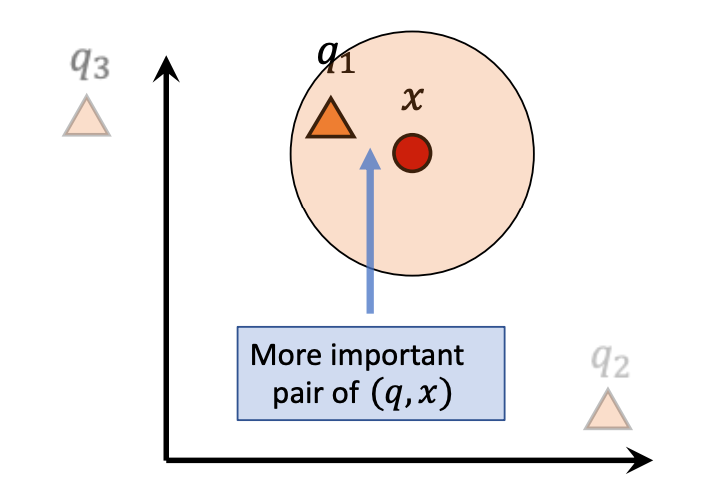

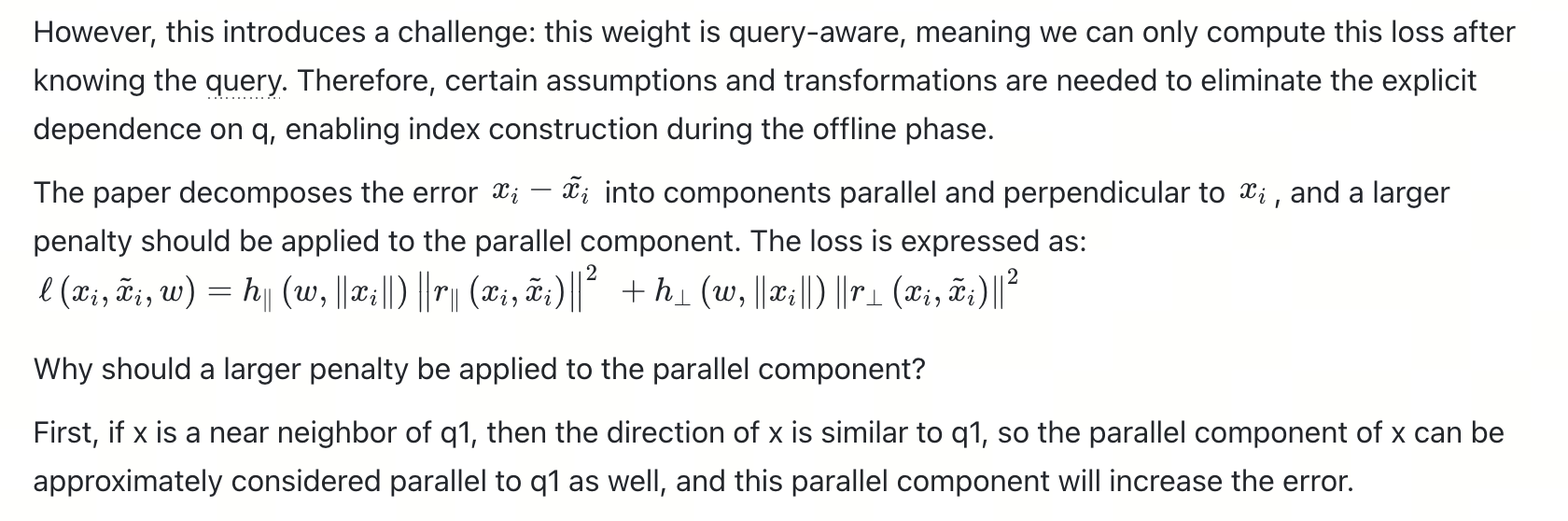

Since the analysis is based on the IP metric, after ScaNN decomposes the quantization error into parallel and perpendicular components, only the parallel component affects the result, so a larger penalty term should be applied. Consequently, the loss function can be rewritten as follows:

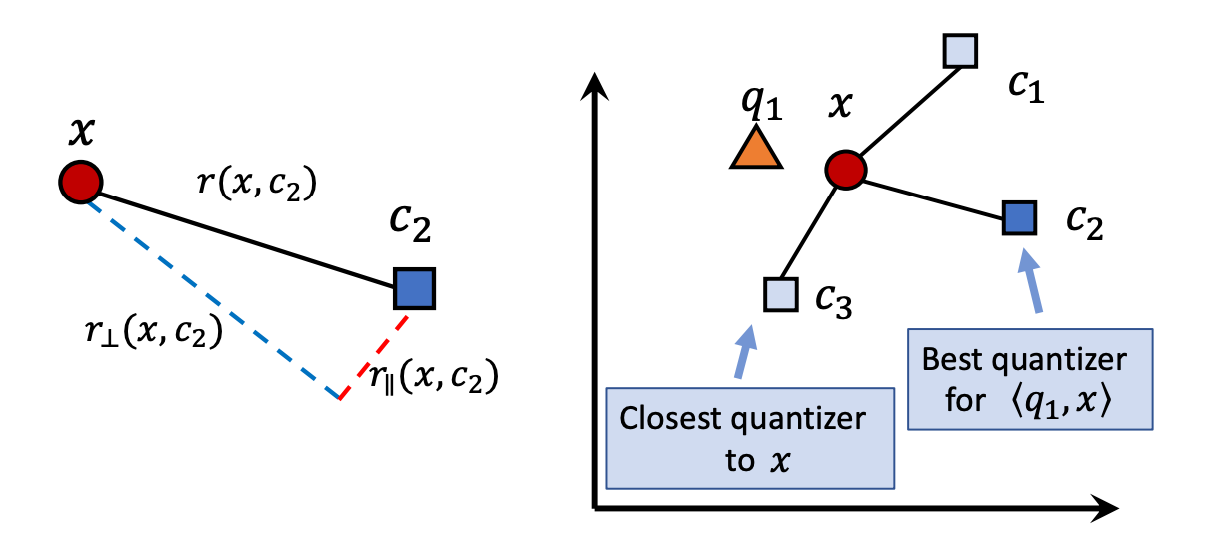

The figure below shows a two-dimensional example illustrating that the error caused by the parallel component is larger and can lead to incorrect nearest neighbor results, thus warranting a more severe penalty.

The left figure shows poor quantization because the parallel offset affects the final result, while the right figure shows better quantization.

The left figure shows poor quantization because the parallel offset affects the final result, while the right figure shows better quantization.

4-bit PQ FastScan

Let’s first review the PQ computation process: during querying, the distances between the query and subvector cluster centers are pre-computed to construct a lookup table. Distance computation is then performed through table lookups to obtain segment distances and sum them.

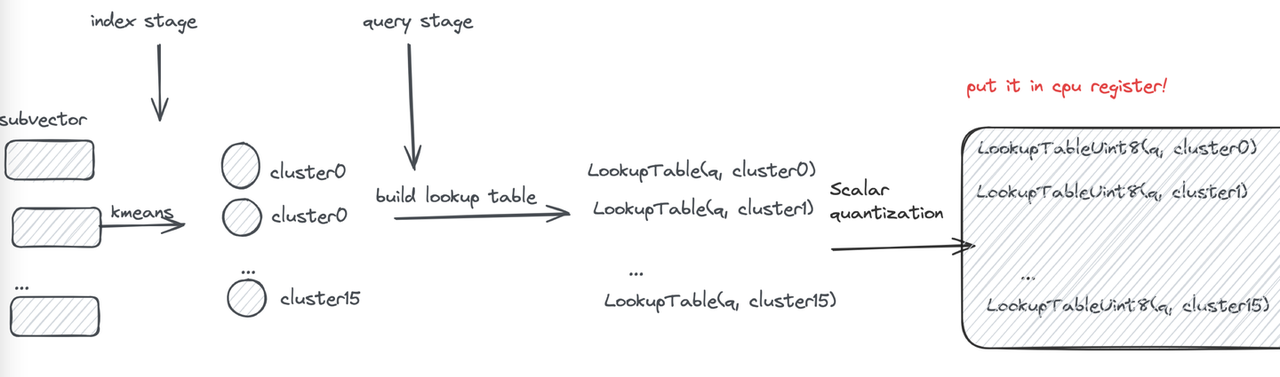

However, frequent memory reads still become a performance bottleneck. If the lookup table can be made small enough to fit in registers, memory read operations can be transformed into efficient CPU SIMD instructions.

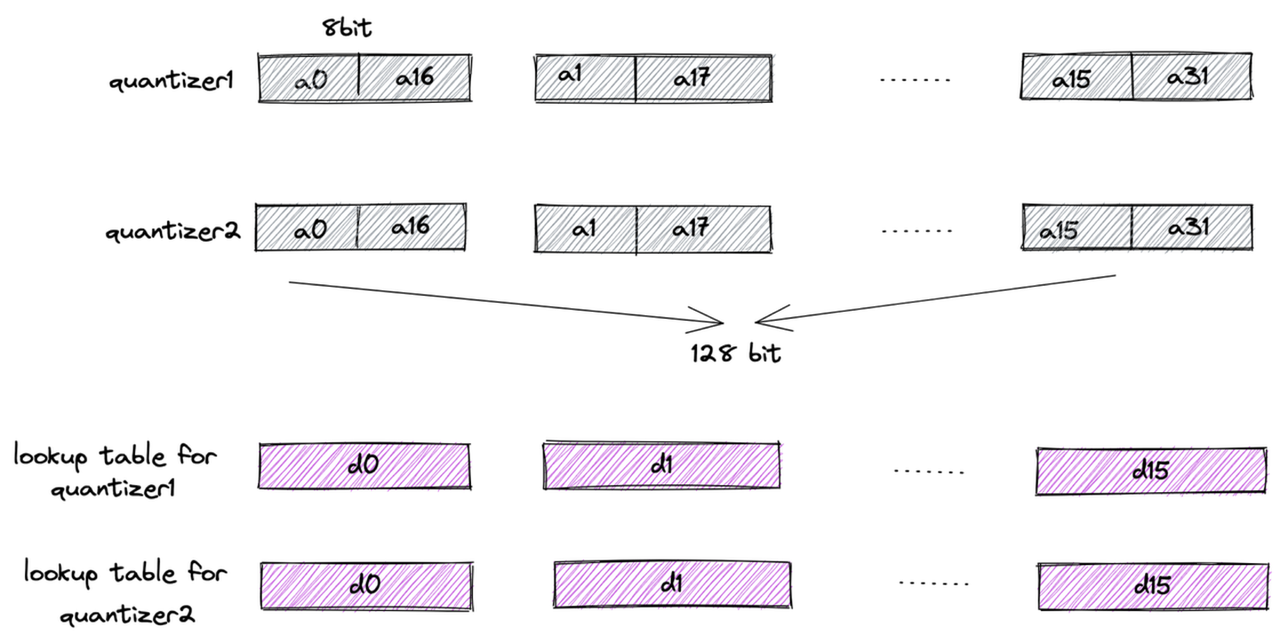

First, each subvector is clustered into 16 classes, so a 4-bit value can represent a cluster center—this is the origin of the name “4-bit PQ.” Then, distances typically represented as floats are further converted to uint8 using Scalar Quantization (SQ). This way, the lookup table for one subvector can be stored in a register using 16 × 8 = 128 bits.

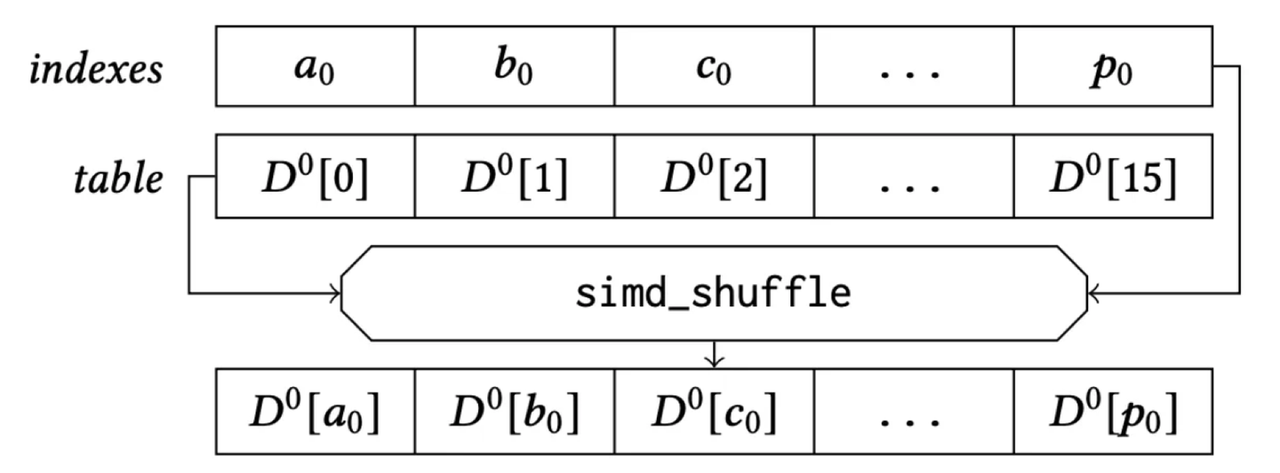

Finally, let’s examine the register storage layout (using AVX2 instruction set as an example): the subvectors of 32 vectors are placed in a 128-bit register, combined with the lookup table. The “lookup” operation can then be efficiently completed using a single SIMD shuffle CPU instruction.

register layout

register layout

SIMD Shuffle for Lookup

SIMD Shuffle for Lookup

Here’s an interesting observation: the ScaNN paper focuses entirely on the first optimization, which is reasonable since it can be considered an algorithm paper emphasizing mathematical derivations. However, the experimental results presented in the paper are remarkably impressive.

The experimental results presented in the ScaNN paper.

The experimental results presented in the ScaNN paper.

Intuitively, optimizing the loss alone should not produce such dramatic effects. Another blog has also pointed this out—what really makes the difference is the 4-bit PQ FastScan portion.

Experimental Results

Using the vector database benchmark tool VectorDBBench, we conducted a simple test. ScaNN’s performance advantage over traditional IVFFLAT and IVF_PQ is quite evident. After integration into Milvus, on the Cohere1M dataset at the same recall rate, QPS can reach 5x that of IVFFLAT and 6x that of IVF_PQ.

However, QPS is slightly lower than that of graph-based indexes like HNSW, so it is not the first choice for high-QPS use cases. But for scenarios with lower recall, it is acceptable (such as in some recommendation systems), using ScaNN without loading raw data can achieve impressive QPS with an extremely low memory footprint (1/16 of the original data), making it an excellent index choice.

| Index_Type | Case | QPS | latency(p99) | recall | memory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVFFLAT | Performance1M | 266 | 0.0173s | 0.9544 | 3G |

| HNSW | Performance1M | 1885 | 0.0054s | 0.9438 | 3.24G |

| IVF_PQ | Performance1M | 208 | 0.0292s | 0.928 | 0.375G |

| ScaNN(with_raw_data: true) | Performance1M | 1215 | 0.0069s | 0.9389 | 3.186G |

| ScaNN(with_raw_data: false) | Performance1M | 1265 | 0.0071s | 0.7066 | 0.186G |

Conclusion

ScaNN builds on the familiar IVFPQ framework but pushes it significantly further through deep engineering work in both quantization and low-level lookup acceleration. By aligning the quantization objective with ranking quality and eliminating memory bottlenecks in the inner loop, ScaNN combines score-aware quantization with a 4-bit PQ FastScan path that turns a traditionally memory-bound process into an efficient, SIMD-friendly computation.

In practice, this gives ScaNN a clear and well-defined niche. It is not intended to replace graph-based indexes like HNSW in high-recall settings. Instead, for recall-insensitive workloads with tight memory budgets, ScaNN delivers high throughput with a very small footprint. In our experiments, after integration into Milvus VectorDB, ScaNN achieved roughly 5× the QPS of IVFFLAT on the Cohere1M dataset, making it a strong choice for high-throughput, low-latency ANN retrieval where compression and efficiency matter more than perfect recall.

If you’re interested in exploring ScaNN further or discussing index selection in real-world systems, join our Slack Channel to chat with our engineers and other AI engineers in the community. You can also book a 20-minute one-on-one session to get insights, guidance, and answers to your questions through Milvus Office Hours.

- IVFPQ Recap

- How IVFPQ Works

- ScaNN Optimizations Based on IVFPQ

- Score-aware Quantization Loss

- 4-bit PQ FastScan

- Experimental Results

- Conclusion

On This Page

Try Managed Milvus for Free

Zilliz Cloud is hassle-free, powered by Milvus and 10x faster.

Get StartedLike the article? Spread the word